AI will soon become commonplace in Cleveland’s classrooms

Urban school districts such as Los Angeles, Baltimore, and New York quickly blocked Chat GPT — the online essay-writing chatbot that recently took the internet by storm — on school devices and networks. These districts have raised concerns about the software’s ability to help students with fraud and plagiarism, as well as the security and accuracy of the content it creates.

But Cleveland schools approach it differently.

Instead of blocking AI software, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District is starting to experiment with different ways to incorporate it into learning and teaching.

“Instead of [of blocking these technologies]The district is focused on helping students and adults recognize and use these tools as productivity tools, knowing they will exist in the world our alumni will live in,” the district said in a statement.

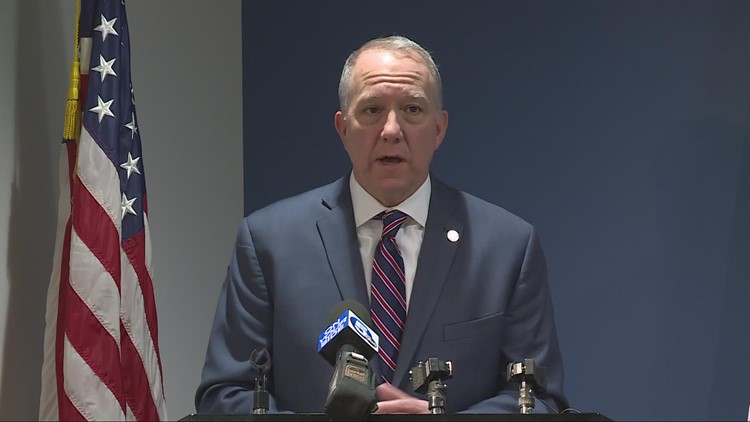

County CEO Eric Gordon compared the recent advent of AI to the advent of smartphones and calculators. In a recent livestream, he said that none of this is going away anytime soon and that the Clevelands need to stay ahead of the curve to figure out how to use it constructively.

“It will happen. And so the question is, how do we responsibly approach this?” He said.

The district has already begun to do this by piloting a select few AI programs in the classroom.

Meet Amira

Whenever Gordon talks about AI, he mentions one particular technology that he says the district has been successful with.

She is an AI character named Amira whose goal is to improve the literacy rate of students from Kindergarten to Third Grade.

She appears as an animated figure wearing a skirt and a green sweater, standing in front of a chalkboard in the upper right corner of a student’s tablet or laptop screen.

Amira listens as the children read the passage aloud, analyzes their speech and gives real-time feedback.

If the student mispronounces a word or makes a mistake, he makes a gesture with his hands and explains the problem, to put it mildly, what the correct answer should be.

See Amira in action here.

Amira can be used in the classroom as a standalone activity, but will also be available for students to use at home on their school devices.

Gordon said CMSD is testing the app at four schools this spring and students are loving it. The district may expand the program to more schools next year. He explained that this would accompany and not replace face-to-face literacy and tutoring.

Amira is an example of educational technology, or edtech for short, a growing field of technology aimed at improving teaching and learning. Amira was developed and tested at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, which has a master’s program in educational technology.

The city of Cleveland has proposed legislation that would use a portion of the city’s American Rescue Plan Act dollars to ferry Amira throughout the area. The law is still awaiting council approval.

AI for teachers

CMSD is also currently experimenting with a small group of teachers on using AI to create blocks and lesson plans.

Gordon detailed this new development in his keynote this week. Teachers have experimented with asking an AI bot to develop lesson plans based on specific student and class profiles, themes, and other parameters.

“They show how we can use it as a production tool,” he said.

Signal Cleveland has asked CMSD for details on the specific software the teachers are using, but has not received a response.

Signal Cleveland also reached out to Cleveland Teachers’ Union President Shari Obrensky, who said that while teachers are not worried about the topic yet, the “AI specter” is definitely around the corner.

CEO Gordon said that AI and educational technology are becoming the subject of serious conversations about education across the country. He said that CMSD will participate in a working group on the topic, organized by the City Council of Schools, the national organization of urban school districts. The task force will develop guidance for school districts when it comes to the responsible use and monitoring of new technologies.

What do the experts say?

Some of the most common problems associated with these technologies relate to the collection and use of student data, as well as the fear that technology can replace good interpersonal learning. Signal Cleveland spoke to several experts for guidance on how school districts, teachers and parents should navigate this new era of technology in schools.

AI should complement, not replace, good learning

Gabriel Swarts, associate dean of education at Baldwin Wallace University whose research has focused on educational technology and educational AI, said teachers should handle new technology the same way they handle a new class schedule or a different test than they are used to. use. .

Swarts told Signal Cleveland that programs like Amira should be used as tools for learning, not as a substitute for learning. And just like any other tool like a calculator, there are times when its use makes sense and there are times when it doesn’t.

“[Amira] can be good for a kind of repetition of vocabulary words, teaching phonetics. You know, some of the basics… but sometimes you mean what you say and they ask you to correct something or put in a different word, and that’s not the tone of conversation you want to use,” Sworths said.

But the bottom line, he says, is that the main thing that contributes to student learning is a great teacher who can make decisions about when and how to use technology.

“Having a good teacher is far more important to the districts’ investment. We cannot get caught up in technology replacing what a great teacher can do,” he said.

Teachers and school districts should be wary of data privacy

Chris Astle, education strategist at education company SMART Technologies, told Signal Cleveland that while apps like Amira can be powerful tools that can personalize learning, they depend on collecting massive amounts of data from students.

This means that there is a potential risk of disclosing student addresses and grade information or selling contact information to third parties.

“Our students are unable to protect themselves and often do not know if their data has been compromised until they are much older, so data security should be a focus for teachers, education leaders and parents alike. ”

Estle said school districts, parents and families can get a better idea of how secure the app is by researching learning technology companies through questions such as:

- Do they encrypt user data for my product? (in transit and at rest)

- How long do they keep my data? What is my data used for?

- Can I request deletion of my data?

- Which employees, contractors and suppliers have access to my data?

- Are they part of the Student Privacy Pledge?

Estle also recommended that schools and families balance interactions with AI, which may seem isolating to some students, with face-to-face interactions with peers and caregivers.

AI and other educational technologies can help personalize learning for students working at different levels

Cleveland State University professor Claire Hughes-Lynch said artificial intelligence and educational technology can be a tool to help teachers tailor their curriculum to better serve students who learn in different ways and at different speeds.

As a professor of special, gifted and twice exceptional education at CSU’s College of Education and Public Affairs, Hughes-Lynch has worked with various types of assistive and alternative technologies in the classroom to help students with a variety of disabilities.

“Over the past 20 years, there has been a huge growth in this technology that has gone mainstream,” she said, “but it has come about because of technology for people with disabilities.”

Hughes-Lynch told Signal Cleveland that technology like Amira can help students with different reading levels because of the instant feedback it provides.

“I see this as a really powerful application, especially because it is tailored to each child, rather than group learning where some children may be excluded… I see great promise in it for children with dyslexia or for talented children. in the field of reading and I want to work further.”

The Amira Learning web page claims that in less than 10 minutes, Amira can screen a student for risk of dyslexia.

On top of all these benefits, Hughes-Lynch said important communication can be lost with technology like the Amira if used as a substitute for training.

“During COVID, we discovered that computers are just not very good at copying teachers, that kids need a teacher, and they need relationships and social-emotional connection with the content that is being provided to them. The avatar can be cute, but it’s not a relationship.”

News Press Ohio – Latest News:

Columbus Local News || Cleveland Local News || Ohio State News || National News || Money and Economy News || Entertainment News || Tech News || Environment News